A Chinese friend once responded harshly when asked, “Are you Japanese?” by a young child who had approached him on the street. His response struck me as strange. After all, my identity was always a topic of discussion. As a child of a Chinese-American father and Caucasian mother, I looked neither. I have thick dark hair, a long nose, large eyes, and slightly colored skin. In fact, I was more often mistaken for Hispanic or Native American rather than Asian or white. My identity was discussed among close friends, acquaintances, and even with strangers who I bumped into in a bar or with whom I had a brief encounter on the street.

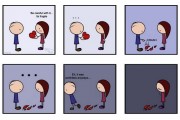

Plus, I got it all the time. Meeting someone for the first time usually meant that he or she might give me that slightly elongated, curious gaze, which was followed by an awkward “I’m sorry..I can’t tell, are you [insert misconceived identity here]?” Or, in contrast, when meeting someone Asian, my appearance wouldn’t merit a second glance, but my last name would always surprise them. “Wait…. why do you have a Chinese last name?” they might ask. In time, I got used to it, like a high school graduate who puts up with questions like “What are you going to major in? What do you want to do when you graduate from college?” You know people are good intentioned and genuinely curious, but when you answer the same question to all your relatives, family friends, teachers and random acquaintances, you still answer out of courtesy, but each time you draw a deeper sigh as you prepare your now well-practiced response.

As a child living in a largely homogenous neighborhood, I quickly figured out that I was different. A name in a different language meant that I knew what to anticipate on the first day of class when the teacher read out the student roster. Every year, the teacher would read my name aloud, awkwardly, and look up at me as if to make sure she hadn’t completely offended me with the reading of my name. The truth was, it didn’t bother me, and I used to make fun of classmates who mispronounced my name. I was too young to be bothered by being the only Asian in a classroom, and was even proud of it. I mean, hey, I got cash on Chinese New Year, what did you get?

And yet, once I moved to a school system with more Asians, the issues surrounding my name disappeared, but somehow I remained distant from the Asian community. When discussions of diversity or multiculturalism were raised, I received slight nods from my white classmates, but I was never close with other Asian students. There was no animosity, we just weren’t friends. Every year, I sat in the K and L section of our alphabetically organized classroom, with the other Lius, Lus, Kohs, and Kangs. They were nice enough to me, but didn’t turn back to chat when the teacher wasn’t looking, nor did I feel comfortable hanging out with them in the halls during break or in the cafeteria. It was with slight envy that I regarded the few other mixed-blood students who were able to conjure up friendships with them. Yet, I couldn’t help but notice how they stuck out, and how they got the occasional confused glance from others, both Asian and otherwise, as if to say, wait… you’re hanging out with them?

But to me, this was never an injustice or something wrong with the world, but simply the way things were. There was no vocabulary in which to articulate my existence. There was no national movement with which to identify. And as I grew older, I shrugged it off. I mean, didn’t middle school suck for everyone?

This all changed once I set foot in college; there was a blossoming of expression and awareness. Suddenly, we were one. Organizations and clubs formed to challenge preexisting notions of race, and ran discussions, published magazines and held conferences on the multiracial experience. Being biracial went from being a footnote to being something one could flaunt, something fashionable.

Yet strangely, I grew tired of this discussion. I went to one diversity awareness event, and visited the multicultural session, structured as a reenactment of what mixed blood students encountered in high school. I entered a mock cafeteria and students representing the black table, Asian table and white table, and turned you away, saying you weren’t black, Asian or white enough to sit with them. C’mon, I thought, of course some people think like that, but what an over-dramatization.

The organizers invited me to come to their weekly meetings. I signed up for the mailing list, but I never made it to a meeting. What is the point? I thought. At that time, I could already select multiple races on my test forms. I get curious glances, but people are open when I talk about my background. Did they talk about being mixed-blood at these meetings? “How long could that discussion last?” I wondered. I mean, what would I, a son of a Chinese father and white mother, have to relate to someone whose mother is Native American and father is black?

Other discussions of Asian identity, how we are lumped into one group, seen as coolies or laundromat owners, as well as the existential question “Who am I?” struck me as mundane. My identity was always a topic for discussion, even when uninvited. I had learned to laugh it off, to joke about it, or take it as an opportunity to discuss my identity with someone who was genuinely interested.

But while I shoved off campus activism, I was involved in my own way. I made time to travel to Minneapolis to see performances at Mixed Blood Theater, which put on both thoughtful and satirical pieces on race and identity. I sat front row when my Latin American history professor discussed the role of mulattoes, the children of indigenous and European parents, and their unique role in governing the colonies.

After graduation, I came to China. Here, I see many of the same responses to my identity. Acquaintances struggle to equate my name with my appearance, and I get the occasional stare from curious onlookers. Half the people I meet mistake me for an ethnic minority from far away provinces. And of course, I am often seen as an outsider, a non-Chinese, which, on the surface seems counter-intuitive, but upon further reflection mirrors what I experienced in the United States and my status as either a minority or an ethnic ambiguity.

So where does this leave us? As for me, I have long ago made my peace with the fact that I will have to be prepared to field questions about my identity at any time. The way I see it, if you are uncomfortable with that, you will have a lifetime full of uncomfortable conversations. But for the mixed-blood community, if we believe there to be one, we have attained our goals of multiple choices on test forms and increasing awareness as the topic of multiracial identity has entered mainstream discussions. Now that we have accomplished this much, we are left with the lingering question: “What’s next?”

For some, they are content to establish that they are different thus special. But are we content to let our DNA, one of the things that we have no control over and contribute nothing toward, define us? Surely there must be some way other than flaunting our ethnicity that we can promote greater understanding across the various lines that divide us, whether they be cultural, racial or religious. Some feel that all one needs is to be a contributing member of society. Do that, the reasoning follows, and others will see you as an individual, not as what you check on the census form. For others, only when we lead people into discussion and introspection can we gain acceptance.

I can’t prescribe the right answer for every individual. After all, what do any two mixed-bloods have in common anyway? But at the least, when someone approaches and asks oh so audaciously what we are, maybe we can withhold the urge to sigh and roll our eyes, and instead summon the strength to give them an honest answer, whether it be the first time or the five hundredth time we’ve heard that question.