In my 20-plus years, I’ve only encountered one other person named Lilach (lee-lok).

The peculiarity of my name is compounded by my last name, Brownstein. So when I introduce myself, people almost always ask two questions: what does your name mean, and where are you from? (Actually three, since they first ask me to repeat myself.)

When I was 10, I wanted to be Jewish.

Thankfully, I’ve had extensive practice pronouncing my name, but the other two questions are difficult to answer. Do I tell them that my name means “lilac” in Hebrew, or that I was named after a deceased relative as per Jewish tradition? Do I say that I’m from Hefei, China where I was born, or Israel where I grew up?

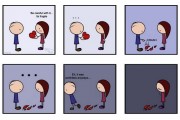

These seemingly light questions dip into murky waters. If I am a boat, then identity is a choppy ocean. I am too preoccupied with staying afloat to consider where I am. Multiple times I thought I knew where I was, but found myself disoriented by the tides.

When I was 10, I wanted to be Jewish. I moved to America, and my mother enrolled me in a private Jewish elementary school. My parents were Jewish, my friends were Jewish, and my parents’ friends were Jewish. I spent half the day in religious studies classes. I attended after-school programs at the Jewish Community Center. These were the only waters I knew; naturally they were the only ones I wanted.

The jokes about my non-genuine ethnicity stung…

When I was 15, I wanted to be Asian*. I had moved to New Jersey after elementary school and made the switch from private to public school. New Chinese and Chinese-American friends introduced me to the world of manga, anime, and country-specific pop music (here’s looking at you, C-pop and K-pop). I thought my heritage would naturally entitle me to claim them as my own. The jokes about my non-genuine ethnicity stung but only fueled the desire to prove myself worthy of the title.

When I was 18, I wanted to be Chinese. I had finally returned to China a few years prior and was overwhelmed by the sense of belonging to the majority. But I wanted to belong by more than appearance alone. In college I began studying Mandarin. I joined a Chinese students association; I considered pledging an Asian sorority; I auditioned for a Chinese a cappella group. My Chinese-ness was a label emblazoned across my forehead.

When I was 19, I wanted to be a Chinese adoptee. The summer after my freshman year I found myself in China once again for an immersion program. I left feeling too American to be solely Chinese, but the Asian American studies class I took the following semester taught me that Chinese-American was also ill-fitting. Not until my final paper on Asian adoptees did I find something more familiar. Calling myself a Chinese adoptee was an admission rather than a desire, but for the first time I was drifting with the current rather than against it.

My Chinese-ness was a label emblazoned across my forehead.

Now I am 20, and I want to be myself. I am both Chinese and an adoptee and much more than that. And though in other ways I am as unsure of myself as I was one, two, five, or even ten years ago, now I am less afraid of my uncertainty. In the past I harbored anger and regret at myself and others, but I have since realized that these growing pains have brought forth the person I am today.

I do not doubt that if I were another boat on another ocean, I would still face obstacles. Conflict is an integral part of the human experience, one without which development could not occur. And it is not always resolved either: the waters around us will continuously try to drown us and we must choose again and again whether to submit or fight.

Often we are so concerned with our own vessel that we never stop to look around and see others are on their own journey. All I hope is that my tiny path in the ocean might help others navigate through similar journeys.

So go ahead, ask me about my name. Just don’t expect a short answer.

Lilach is part of Project Pengyou, where she is projecting her aspirations on a larger scale developing a network for Americans with experience in China and promoting cross-cultural exchange. She wants others on similar paths to know that not being sure of their identity is perfectly acceptable.

* – Please excuse my use of the umbrella term “Asian” for the sake of brevity. I am aware that it is vague and while there are commonalities among different Asian cultures, there is not one “Asian culture.”