I’ve met many people from all around the world, and I found out how different, in many instances, frames and modes of thought are, simply due to entirely different upbringings. Once, on a school field trip to a garden I met a white woman in her forties and she made conversation with me. Eventually she asked, “So… What are you?” and I knew from her tone of voice what kind of answer she wanted. I’ve been asked this question many times and she probably expected me to say that I was Chinese, but I decided to indulge myself and give her a full answer, hoping she would understand.

I am ethnically Chinese and I was born and raised in America; but the story is much more complicated. My great-grandparents are from Shantou, China, but they immigrated to Cambodia. It’s in Cambodia that my grandparents were born, but they continued to marry other ethnically Chinese families within Cambodia. My ethnically Chinese parents were then also born and raised in Cambodia, married each other, and then because of the Khmer Rouge (the genocide in Cambodia) they eventually immigrated to the United States. So here I am now, still ethnically Chinese, culturally Cambodian, but also American because I was born and raised in Seattle.

I told her this story and then she pauses and tells me, “So you’re really just Chinese.” This attitude is one I get quite often, and it’s really infuriating. I just gave her my background so I could avoid the “You’re only American” or “You’re only Chinese” kind of answer. I know she didn’t mean anything by it, but I come across this kind of person all the time. Most non-Chinese Americans see me as Chinese first and foremost, while most Chinese people will see me as American first and foremost. Does the language I speak at home, the culture I abide by, or the fact I was born and raised in America not count for something? I’m not entirely either Chinese or American, but if I’m neither both then what I really am is nothing more than a blank state. It’s frustrating when someone you don’t know tries to steal a piece of your cultural identity.

My grandparents raised me to speak Chaozhou Chinese and it’s from them that I acquired many Chinese traditions, and keeping in mind that they and my parents were born and raised in Cambodia means that I also picked up many habits and traditions from Cambodian culture. There is much difficulty in maintaining cultural identity in America. Once I step outside home, it becomes an entire new world with an entire new set of rules. To say I’m Chinese is only part of the answer. The fact is that I grew up in a western society so the way I think and act is obviously influenced by western values and my English is better than when I speak Khmer or Chaozhou.

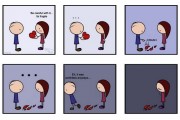

As a small child I went through many phases trying to deal with my identity crisis, for a while I attempted rejecting American culture altogether, then attempted rejecting Chinese culture, and then rejecting Cambodian culture. I lived in constant paranoia. I tried hard to be one or the other, my whole life to fit into a mold that I never would be able to fit into. Then out of the blue people like the woman at the garden come and label me however they like, forcing me to realize I’m not entirely Chinese or American but because of my face I’m still held to Chinese standards. My grandparents always pressured me to be Chinese and that being American and adopting American views is shameful, while outside home, it was implied I should assimilate into American culture so I would “fit in”. The conflicting views pressed upon me were painfully stressful.

Then in high school I began studying Mandarin Chinese through OneWorldNow (an afterschool program that teaches Chinese or Arabic) and I was introduced to the culture in an entirely new way. I studied really hard and I can now hold conversations in Mandarin. When I graduated high school I got a scholarship to study abroad in Shanghai, and it was in China where I really realized both how American and how Chinese I really am. It was an amazing and wonderful experience, and frustrating too. Whenever I traveled with my other American friends, locals assumed I was a tour guide and spoke to me first. When I was with Chinese friends, I received disparaging comments on how poor my Mandarin was, despite having only studied for 2 years. Having living my entire life in America and then going to study in China was exactly what I needed to solidify who I am.

I am the product of when East meets West – a living example of cultural dispersal. I’ve learned to stop looking for other people’s approval of my identity and to try creating an identity unique to me in which nationality and ethnicity are not the foremost parts of my identity. My identity is my own and I decide who I want to be, and yes, the fact I am Chinese or Cambodian or American is just a small part of who I am and no one can change that.