Growing up, I never thought much about my Chinese heritage. Despite Saturday mornings at Chinese language school and living next door to my grandparents—who fled China with the Kuomintang during the civil war—my main interest in my “Chineseness” was in wondering why was I Chinese? How was it that I had an unpronounceable name and no one else? Who was this Sun Wukong and why did I have to watch his exploits? In my elementary school, there was one other student who spoke Mandarin, and we avoided each other like the plague so as not to be too obliviously branded as outsiders.

The Chinese community in Minneapolis was a small one. I think I may have seen my schoolmate at one of the many social events that Chinese families flocked to. Meeting the friends and acquaintances of my parents only solidified my belief that I had very little in common with those people. These gatherings and the people at them were not a part of who I was. I was only there because of the randomness of ancestry. I didn’t loathe my background; at worst I scorned it. It was clear that all things “American” were naturally superior to anything “Chinese.” At best, being Chinese was simply inconsequential to who I was as a person. The only times I would actively attack our family background was as a means to offend my father, who had come to the United States in his 30s and represented the catchall idea of the “Chinese.”

As the years passed, my time at Chinese school ended and the links to that world grew even fainter when my grandmother returned to Taiwan following the death of my grandfather. I was happy to embrace the American aspects of my life, though there was always a slight unsettled feeling at the edge of my consciousness. Like I knew that I never fully belonged. But I ignored it and pushed on. At university, passing a foreign language proficiency test was a requirement for graduation. Despite knowing that learning new languages was not a strong suit, the unhappy memories of my Saturday mornings in Chinese class led me to try Latin, and finally settle on sign language as my language of choice.

I passed the proficiency test, graduated, and after a few years of working, decided to join the Peace Corps. Though initially unenthusiastic about the thought of his only son volunteering for two years doing development work in a far off country, my father eventually suggested I try to get sent to China, which has a small Peace Corps presence. But in the same vein as my resistance to studying Chinese at university, the idea of going to China held no interest for me. And besides, my sights were set on Africa. I was eventually sent to the Republic of Cape Verde, a small archipelago of ten islands off of the west coast of Senegal. Once in country for training, I quickly learned that the Cape Verdeans were well acquainted with the Chinese.

As the story goes, sometime in the early 1990s, a Chinese businessman from Wenzhou who was based in Africa sent two of his nephews to Cape Verde to see what sort of business opportunities might be found. Nothing interested him, but his nephews opened up a small store selling household goods and clothes. Their initial success led them to lure over family and classmates from Wenzhou, who then repeated the cycle. By the time I arrived, there were over one thousand Chinese operating 300-odd shops throughout the islands.

I was assigned to a community that, over the course of my time there, saw the establishment of three Chinese shops (or, “loja Chines” in the local language). Four Chinese shopkeepers ran the lojas. They were all recent arrivals to Cape Verde and the distances they were willing to travel and the sacrifices they made as they chased opportunities to the edge of the Atlantic fascinated me. I had no romantic notions regarding their motivations for being there. It was simply money and business. And their aspirations for a better life for themselves and their children are part of the same story told by waves of immigrants throughout history. But these Chinese from Wenzhou stuck a different, much more resonant chord in me. Perhaps because I was seeing their stories unfold up close and personal? Or maybe I could see traces of my own family’s history in their stories? As a result, I began (perhaps for the first time) to grasp the scope of the struggles and achievements of my parents and grandparents, in their quest to build a new life for themselves in a distant land.

Though I was in Cape Verde to immerse myself in the local culture, there were times I was focused on creating stronger connections with the shopkeepers. We discussed their lives in China, the culture of the Chinese in the U.S., and daily life and the goings-on in our community. That scorn I had for all things Chinese had disappeared, having been replaced with a deep and almost unexplainable urge to absorb as much as I could from the shopkeepers. I wasn’t just trying to explore a culture I had a passing familiarity with, I was trying to better understand a part of myself that I had ignored. The way these shopkeepers saw the world reminded me of what I heard from my parents—especially my father. Their conversations led me to better appreciate the mentality of my parents and the decisions they made for me as I was growing up.

For all the insights I gained and the interest that was awakened in me, language still limited the amount of communication we had. My Chinese had grown weak over the years, which wasn’t a problem in the U.S., because I could simply insert an English word or two into an otherwise Chinese sentence. But that wouldn’t work with the shopkeepers, whose knowledge of the local language was commerce-centric, and thus ensuring our encounters always to be in Chinese. So my time in Cape Verde was also marked by the daily use of Chinese – something I hadn’t done since living next to my grandparents.

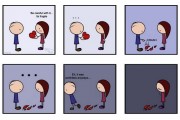

So an unlikely result of my time in Africa was my improved Chinese skills. I also rediscovered something of myself. You might think that this new found desire to reconnect with what I’d disregarded for so long would create some sort of resolution for me but, instead of settling that unsettled feeling, it only stirred up more issues about myself. And it seems that my father—who has now spent an equal number of years in Asia and the West—anticipated this years ago. A Chinese relative recently visited him and asked if my father considered himself Chinese or American. My father replied that when he saw Chinese people doing something he didn’t like, he thought of himself as American. But when he saw Americans doing something equally disagreeable, he considered himself Chinese. My father wanted me to avoid this fate, so he decided to allow me to grow up as an American, and not have to choose between that and the Chinese.

But my time in Africa made me realize that even with a primarily American upbringing, I would never fully fit into one world, and would always be caught between them. Cape Verdeans had a hard time believing that someone with the shape of my eyes and the color of my hair could be American. To the shopkeepers, I was a bit of an oddity that spoke Mandarin, but how could I be one of them if I didn’t understand that in the heart of every Chinese laid a dragon? And no matter that I was born and raised in the U.S., it never escapes notice that I am not a full, unhyphenated American.

So here I am, too Yellow to be American, and too White to be Chinese. Though I’m lucky to be the child of two cultures, where this leaves me, I’m not totally sure. The path I took from Africa to a rekindled the interest in my Chinese roots is perhaps unique. But what’s more common is the struggle that many face in reconciling the mix of cultural and ethnic backgrounds that make up who they are as a person. When others ask me about my background, I can say Chinese-American or Huáyì. But does this really explain anything about me? Sometimes, I can barely understand what those words imply. How, then, can someone else nod their head and truly comprehend?

I am American. I am not. I am Chinese. I am not. Someday, I’ll figure out what I am. Or maybe not.