When I was seventeen, I became an American citizen. The woman from Immigration Services sat across a broad desk and asked me to name the third president. When I did so swiftly—after all, my high school was named after him—in a standard American accent she seemed surprised and said, “Oh, you’re an American.” Well, not technically.

Instead of asking me more questions—my mom had been posed three, including, “What was the main reason over which the Civil War was fought?”—she pulled out a piece of paper and told me to sign it. It began, “I hereby declare, on oath, that I absolutely and entirely renounce and abjure all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince, potentate, state, or sovereignty of whom or which I have heretofore been a subject or citizen…” As you might imagine, this was a lot to take in for a seventeen-year-old. What exactly was being asked of me here? I knew I was technically a foreigner, and, if we’re being really technical, a subject of the People’s Republic of China, but did I have any allegiance and fidelity to that country? It was an ocean away and I hadn’t visited in years. I looked at my Chinese passport. I had never liked its shade of burgundy but now, faced with having to relinquish it, I felt a pang of distress that I had not cherished it more.

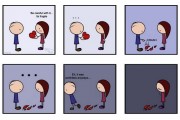

I signed the paper. The woman took my passport—or had I handed it to her, like Abraham offering up Isaac?—and put it in her drawer and that was it: I was an American.

I waited for a sign—a chorus of angels, a burst of light—but there was nothing. I was still me, and the world kept quietly turning. My mother picked up her purse and we drove home. Two weeks later I received a new passport in the mail. It was navy blue and I couldn’t help thinking that I liked this color better than that rusted burgundy.

Five years later, after college, I came back to China on a lark. I wanted, as in an old bildungsroman, to find out who I was. But I quickly discovered that my identity confused people. A common conversation went like this:

“Are you a Chinese?”

Well, I was born in China and moved to America when I was very young.

“So you’re an ABC.”

Not quite. ABC stands for “American-born Chinese” and, as I just explained, I was born in China, so I guess, if you had to, you could call me a CBA, a “Chinese-born American.”

“So you’re an American?”

That depends on what you mean by “American.” I have an American passport.

“You talk like an American.”

Well I have lived there for nearly two decades.

“So you’re Chinese-American.”

I guess you could say that.

“But you look Chinese.”

Because I am ethnically Chinese.

“So that makes you Chinese.”

Right.

It was frustrating at first, having people cram me into whatever racial box suited them. I was Chinese so long as they liked me, but if I made a comment critical of China or not in line with “traditional Chinese thinking,” they would counter with the pseudo-rhetorical: “你是中国人吗?”, “Are you Chinese?”

I never knew how to answer that. I can’t blame people for wanting simple answers to complex questions. Chinese people, coming from a largely homogenous society, are used to thinking about race in black-and-white and, because the culture discourages individuality, often conflate the concepts of nationality, race, and identity.

My nationality is American and I am a member of the Han race. But the question of identity is much trickier. I am a product of two cultures, as trite as it sounds—which is to say that I am influenced by two ways of thinking more or less equally. I was raised in a Chinese household but spent most of my day in American society.

This caused problems. When I was growing up, my parents made me go to Chinese school every Sunday from 2 to 4 p.m. in order to learn Mandarin and retain some semblance of being Chinese. I went for ten years. Today, I’m thankful for being able to speak Mandarin as it has helped my work and life in Beijing immensely. But growing up, I tried to get out of it every week. I didn’t understand why my friends got to sleep over on Saturdays and didn’t have to learn another language on the Sabbath.

I think Chinese school, more than anything else in my childhood—more than the dismissive way girls looked at me, more than my lack of musculature or the size of my family’s apartment compared to my friends’ houses–contributed to my sense of not belonging, my sense that I was different, not in a cheesy, unique snowflake kind of way, but that something deep down separated me, irrevocably, from others, and from America.

So when I came to China after college, I tried to see if I could belong here. I decided to do my best to blend in. If I didn’t talk too much, no one should be able to tell me apart—I’d just be another bespectacled Chinese man. And yet this failed spectacularly. After being in Beijing a month, I walked up to the counter of a Dairy Queen and ordered a Blizzard. The girl at the counter asked, “You’re not from this country, are you?” I ask her how she could tell. “I don’t know,” she said. “Something about your 气质 (disposition), the way you walk.” How strange, I thought, after all that posturing, my stride had given me away.

In retrospect, it was foolish of me to think I could belong to a country I had no memories of and had only visited sporadically. But it made me wonder: was there really no place in the world I could call myself a part of? It’s a question I sometimes ponder in the moments when my mind idles before sleep. Did I ever have a choice in who I’ve become? Could any child born in China, brought to the United States at the age of four, and raised there under the strict supervision of Chinese parents, be any different? Then, if sleep still hasn’t taken me, I do a little thought experiment: I tweak the variables of my early childhood and construct my life in that alternate reality. What if I had gone to the United States as a teenager? What if I had been born in America? Who would I be then?

Imagining life in these bizarro worlds makes for somnolent fun but I inevitably arrive at the same conclusion: who I could have been is nowhere near as interesting as who I am now. There’s no one else, and no place else, I’d rather be. Sure, I sometimes feel isolated, misunderstood, and alone, but those emotions are present in every life, not just those of immigrants or minorities.

If anything, my upbringing has made me look for something more than race and nationality by which to define myself. It has made me restless and inquisitive. My want for a sense of belonging made me go out into the world. My failure to find it compelled me to stay there. Most of all, my experiences have made me see that petty human distinctions such as race and nationality, not to mention gender and sexuality, don’t mean anything beyond the physical, beyond boxes on a form and the hue of a passport. They don’t determine anything when it comes to your life and they fall far short in defining who you are. Your identity, like your future, is something you construct for yourself. That’s why there were no angels or bursts of light. I was still me, and the world kept quietly turning.

George Ding blogs at The HyperModern.