Diaspora readers should take a look at Helen Gao’s “Clash of Civilizations: The Confusion of Being a Chinese Student in America,” published in The Atlantic. The article discusses the conflicted feelings of newly arrived Chinese students in the U.S. who are often unprepared for their host country’s hostile and condescending opinions on China.

I read the article with interest and a twinge of guilt… because once upon a time, I was one of those people giving Chinese students a hard time about the place they come from.

***

In 2004, I made my first friend from the People’s Republic of China. Prior to Jen, those I knew who’d been born on Chinese soil had become first-generation Canadians or were landed immigrants who’d been in the country for years. In comparison, Jen was a truly fresh-off-the-plane international student, a foreigner with her heart in Sichuan and her mind set on earning her foreign engineering degree and returning to China to make her family proud.

We were in Toronto one weekend, two vaguely-acquainted friends-of-friends who’d ended up alone together simply because no one else wanted to travel in -25°C weather for fresh egg tarts. The howling snow storm outside the hostel kept us awake that night, and with the new intimacy of travel partners, we started sharing stories of where we came from.

Jen told me about a childhood in China filled with love from her parents and extended family. She told me stories about school, her friends, her doting boyfriend, trips to beautiful Jiuzaigou, her mother’s hot and spicy malatang. She missed Chengdu, she said, and often longed for the bustle of that city of 10 million, such a contrast to our small university town. She laughed at how little she knew about her destination when applying for Canadian universities, an ignorance brought on by a strong reluctance to leave. She had wanted to go to university in China, she said, but her parents insisted on trading their savings for her broadened horizons.

To my teenage ears, Jen’s stories didn’t sound right. Her China certainly wasn’t the China I’d already formed a strong opinion on despite having no firsthand knowledge or experience of the country. China, to me, was the place my ancestors had escaped from three generations ago, a violent mess of a place I’d read about in countless Cultural Revolution memoirs and articles discussing the Three T’s. Jen should have been eager to leave China, determined never to return, I thought. Her childhood must surely have been plagued by the loneliness of being an only child, bad pollution hurting her lungs, academic pressure and the stress of competing with a billion others. Instead, she sounded… happy.

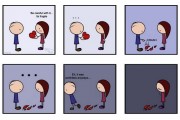

That night, I brought up all my prejudices against China, and tried to goad Jen into discussing certain topics like Tiananmen Square despite my own shaky knowledge of events. She grew increasingly agitated as she listened to my self-righteous rants against the place she called home. “China isn’t like that!” she cried. She told me she was learning more about China by being overseas, but she couldn’t see how the country in which she was born and raised could be so bad. “Why do you need me to hate China?” she asked.

Why, exactly, did I? Why was I trying to offend another? Was I trying to bully her into seeing the light, my light? Did I want to liberate her from the fog of propaganda that I assumed blinded her childhood?

Jen’s simple question rang in my ears every time I felt the need to bring up “China’s problems” with new mainland Chinese friends. In 2007, I had a roommate from Shanghai, who responded to my criticisms with a fierce loyalty to her country that only spurred me on. I’m sure “human rights,” “Taiwan” and “Little Emperors” were thrown in there somewhere. Neither of us were swayed by the other, and we went to bed with our backs to each other that night.

Back then, I didn’t understand why Chinese students would get offended by my remarks, which I thought were fair. But in her Atlantic article, Helen Gao repeats Jen’s sentiments – she, too, “had difficulty connecting the Orwellian China described in western media to the one I recognized,” and thus found herself “wrestling with an instinctive compulsion to take China’s side, a feeling not unfamiliar to many Chinese students in the States.”

Another Chinese friend I met in Canada says he’s “not nationalistic at all,” and only feels compelled to defend his country when baited by those who think in black-and-white. “Only a very ignorant frog in a well would deny China has an ugly side,” he said. “Sometimes I think China sucks. We’re developing too fast, and there are too many problems because of that, but I decided to come back. We’re flawed, not evil.”

***

An American friend argues that the “problem” discussed in Gao’s article is definitely not limited to Chinese students in the U.S. “I get the crap kicked out of me all the time for every sin committed by the United States since Jefferson set his pen to paper and began writing the Declaration of Independence,” he says. Americans abroad are often taken to task for their country’s decisions whether the individuals in question personally agree with those decisions or not, from the war in Iraq to shows like Keeping Up with the Kardashians. Dealing with outsiders’ strong opinions about your country is an unavoidable consequence of being a citizen of a country with a heavy presence on the world stage.

As for myself, I shoved aside all those Mao-era yadda-yadda memoirs of China and decided to see the country for myself. Ironically, I am the one who has settled in China, while my friend Jen is still living and working in Canada. We’ve come a long way from that cold night in a Toronto hostel when she was struggling against my negative views. Today, she’s quite critical of her home country, while I tend to defend China to my parents, relatives, and friends who’ve only been able to experience China through foreign media.

It’s amazing how popping your head out of the well can change you.

Have you ever goaded someone into a critical discussion of his/her country? Have you ever had a negative opinion of a place that was changed after experiencing it?

Christine writes about being an ethnically Chinese foreigner in China at Shanghai Shiok!