Hi, hello. Let’s get to know each other. My name is Alex Tan and I decided to write to Diaspora @ chinaSMACK as part of a journey which began officially 3-4 years ago. The purpose of this journey? To discover if there were more people like me out there, was I unique? What issues/challenges, hopes and dreams did others like me have? Like many other writers on this website I am a mixed-race (Anglo-Chinese) person. I found chinaSMACK a little while ago and the Diaspora site offered a great opportunity to share what I have learned about “Chineseness” and identity, having made it the topic of my PhD 3 years ago.

Before I reveal the recent conclusions from my academic study, I want to give a little background. It was recognising my difference growing up in a small village in England which I can say led me to start enquiring more about Chineseness. Then, I was one of the only non-white pupils, not usually a problem, but I stood out. I only knew the reason being I looked different due to having a Chinese father. For other intents, I considered myself the same as other pupils. But I wasn’t. My difference became clear in secondary school where I remained a minority in terms of having Chinese parentage, despite the school being quite ethnically mixed. Sometimes my ethnicity would form the part of bullying, and recalling being called a ‘paki’, a derogatory term for people from Pakistan, is still a sore memory. Sticking out perhaps naturally drew me towards an outlet which would express my feelings about being different. I found this in music, furiously playing guitar, listening to rock and punk music. Bands like The Offspring, Fugazi, GlassJaw gave me something to hold onto and explore the idea of being different in society. This music though had little to say about ethnicity specifically, and didn’t refer to Chineseness at all…

Fast forward then to 4 years ago. I started meeting more Chinese people from China as an undergraduate and I became really interested in how the notion of Chineseness might be worked out and ‘lived’ for those in the UK. I decided to combine what academics had written with the accounts and experiences of individuals. I used my master’s dissertation to explore some of the themes which interested me and eventually I began a PhD in which I interviewed a number of young British Chinese, asking them about their experiences of growing up, the transitions in life they were making, changes and priorities for the future. The aim was to extend academic understandings of British Chinese young people (16-25) which I have argued traditionally look to racism, social justice issues, the takeaway and education as a focus in research. As I myself knew, there was much more to being Chinese than those four categories expressed; this was not to say they were no longer relevant or important. What though about music? What about family, friends, the vibrancy of life?

The young people I interviewed were not necessarily representative of every British Chinese in the UK. I wasn’t looking for that. Just to open conversation on the issue about the many experiences out there. As a human geographer I believe that where we come from and how we grow up has an important impact on whom we become. I wanted that represented for young Chinese people in the UK. I was still questioning my place within Chineseness in Britain, but perhaps by contributing to discussion I have played a part in that. In particular a personal question was whether there were others like me whom had grown up in isolation from other Chinese people or the issues facing them as a group, perhaps even the norm was something else.

My research was based in Newcastle but in order to understand the differences between Chinese community experiences in the UK I also visited Manchester frequently. Manchester is the largest centre for Chinese people outside of London and the outlets there for Chinese artists and expression on the BBC’s radio Manchester ‘Chinatown’ show also attracted me to give two interviews there. I would suggest readers give the show a listen sometime, the mix of Cantonese and Mandarin music speaks to some of the differences in languages Chinese people in the UK identify with and also features interviews and features on the community.

Like myself, I found many young people were figuring out the idea of being Chinese in a UK context. I did not agree with the argument that there was an inevitable culture clash for young people, sometimes exemplified in terms ‘banana’ or ‘fake Chinese’. The people I met had faced challenges, perhaps bullies at school, rude customers when working in takeaways or even awkward questions from other Chinese people originating from outside the UK. Like all of us though, those I interviewed were living in a globalising world, where locating your self and having an identity are seen as being important to young people, and learning how individuals dealt with this formed the base of my conclusions and findings.

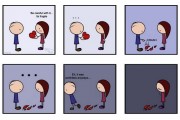

My conclusion was that difference and change are related. We search to find the source of our differences and might look for comfort after rejection; perhaps we seek collectives with others we believe are similar or hold similar experiences. How were young British Chinese people able to explore their identity and related their ethnicity? Living as a minority might mean not having your heritage recognised in schools, on TV, in books. People you meet may only know chow mein and sweet and sour as examples of Chinese food. Perhaps they think Chinese people all come from China mainland as it is today, not realising there are a large number of diasporic family histories, where many young people with these backgrounds may never have even visited China nor their parents’ origin countries. In terms of Chinese experiences in Britain, I looked at four areas:

- Language – usually Cantonese, Mandarin and possibly Hakka. Language was important for communicating with parents, but it also gives a link to countries abroad which might use Chinese.

- Family – parents might not speak much English, one reason to use Chinese to communicate, but this might also mean they need assistance to translate things in daily life. Extended family in the UK or abroad could mean travelling to visit them. Family could be important as the closest Chinese people individuals might know growing up.

- Education – young people often stressed the importance of education, having seen how their parents may have worked hard to get jobs in the UK at a time when employment was difficult for immigrants. Parents wanted their children to have a different life and often hoped they would use education to enter into professional work.

- Leisure – through leisure we might make connections with others around us and learn about socialising. It might be too easy to forget the importance of interacting with others and coming to terms with difference in this way. Listening to Canto-pop for example might allow young people to connect with their parent’s home cities or places as well as with others whom have a similar background.

Out of these, I suggest that for many British Chinese it is their experiences of being raised by parents of Chinese background which brings them to identify as Chinese and to what extent and in what ways they come to view this. So far this might seem like a quite obvious and logical point to make. However, I am keen to note that the parents of many young British Chinese have had quite different experiences of being young compared to their children; many having moved here when they were in their 20s and starting work and families quite early. The British Chinese of the next generation have a different and new set of experiences and interpretations of Chineseness compared to their parents. Chineseness and identity has been explored away from China or Chinese settings, where perhaps pop culture, music from Hong Kong (Canto-pop), anime from Japan, use of English alongside Chinese and a period of extended childhood and adolescence might all combine for an individual. A look at the young Chinese in Britain now has shown me that there is a vibrant and dynamic generation of British Chinese people which are not necessarily confined by racism or inequality compared to other members of the British population, are well educated and often have escaped the catering work many parents have done since entering the UK. Because the society young British Chinese grow up in might not present a lot of places for Chinese language and cultural activities, there were often worries about how Chinese they were, and sometimes this could lead to questioning their identities or feelings of awkwardness.

Having faced some of the same questions and feelings of awkwardness myself, doing the PhD project helped to give me a more open look at the idea of identity. During my PhD I started to learn Mandarin and visited China for the first time. I began my journey 4 years ago barely knowing anything about Chinese people, what Chineseness meant to me or others. I began to investigate Chinese experiences in the UK in my masters. Having looked at the experiences of British Chinese for my PhD I have in some ways been able to locate myself, I am fortunate to live in a country where exploring my ethnicity is possible and perhaps the significance of those four concerns about the Chinese in Britain can be looked at more flexibly and opened to the importance of other experiences young British Chinese have. Hopefully by writing pieces like this and getting others to discuss, individuals won’t have to question their identity alone. Considering the many backgrounds and understandings of Chineseness out there, perhaps keeping conversation is important.