Every overseas Chinese have dealt with this problem in one way or another.

Being immigrants to our newly adopted country, The Philippines, our ancestors must adapt to its lifestyle, culture and of course – its language. Over time, they have come to learn the Filipino language and made it part of their own identity.

A healthy mix of the Chinese dialect — Hokkien and the local Filipino language is common among the older generation Filipino-Chinese. One problem though, this doesn’t necessarily translate to the succeeding generations of Filipino-Chinese.

Unlike our ancestors, we didn’t grow up in the Mainland. Thus, we were not exposed our ancestral culture, tradition and language to the extent that they did. Hence, we naturally would adapt to our immediate environment especially with the language – Filipino.

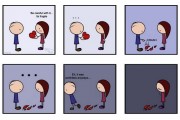

You would think parents and grandparents would understand this predicament, right? But they have a way of giving you a dose of guilt and shame, deliberately or otherwise, by making you feel inadequate because of your inability to communicate in Chinese.

There is a layer of disappointment whenever they have to translate their sentences to Filipino or English when they get your confused look of “what did you just say?”

This begs the question… where is this fine line between adopting your local language and preserving your own?

What languages I actually use (and to whom)

Personally, I speak a mix of Filipino and English 90% of the time. I only use my small arsenal of Hokkien vocabulary with my parents and grandparents as well as their peers.

I couldn’t really imagine speaking in straight Hokkien to anyone of my peers. That would seem the most unnatural thing to do, with the exception of using it as a secret language.

I believe this is true with majority of the Filipino-Chinese. You could only imagine how limited our capacity to communicate in our ancestral tongue is.

Coming from a close family, it does bother me when they say “These children always speak in Filipino, they don’t know how to speak in Chinese anymore” followed by a hint of disdain and disappointment. I consider my siblings and I pretty obedient kids and we definitely love our parents a lot. And it definitely sucks when you feel that you have let your parents down.

It sometimes led me to wonder, “What’s wrong here? Is it really my fault?”

Whose fault is it?

I don’t think it is really anybody’s fault.

As a kid, you don’t really think about your ancestry. You don’t consciously think about what language to use for which situation and to whom. You will use anything just to get what you want, right?

We naturally gravitate to the language that we could communicate our needs and wants most effectively. As a baby, that just consisted of crying and pointing.

In a country where we comprise just roughly 1-2% of almost 100 million people and where the primary teaching methodology in school is in English, one could easily see that’s where we gravitate towards.

For me, it is simply a matter of evolution.

The current generation right now is:

- More educated – There are plenty of Filipino-Chinese doctors, lawyers and other professionals now than ever before.

- More involved – Despite being a minority, Filipino-Chinese have been very influential in the economic, social and political affairs of the country

When it comes down to it, we could be functional, productive and successful without ever knowing how to speak Chinese.

But are these enough reasons to say we don’t need to learn Chinese anymore?

No.

Filipino or Chinese

Here is the funny thing. I have lived my entire life in the Philippines but people would always associate me with my ancestry rather than my nationality. They would ask “Chinese ka? (“Are you Chinese?”) to which I reply yes.

I have been to China as well and have been asked from which Chinese city I came from and I would simply tell them I’m a Filipino. Usually taken with a look of “Is this guy kidding around?”

My point is — we are neither just one nor the other.

Because we are both.

And the PUREST way we associate with our dual identities is through language.

Isn’t that the association we make with people and their respective nationalities/ancestry? He is German/Spanish/French thus he can speak its language. His failure to do so would boggle your mind right?

Thus to say that we can make do without the Chinese language is like saying we are leaving the other half of our identity — HOLLOW.

Let us not forget the reason we are in the Philippines in the first place. Our ancestors needed to leave China to provide a better life for their families. They migrated with the little possession they had and were simply fueled by their big hopes and dreams.

Language is the fiber of their community as a group and identity as an individual. And to simply treat the Chinese language as an after-thought is like disregarding their struggles and our history.

Which Chinese to learn? How do I fit it in my life?

All of us want a sense of approval from our respective families by improving our Hokkien. But I believe what they would truly be proud of is that if the current generation proactively pursues the study of Mandarin Chinese, as it already has an established system of instruction and has wider reach internationally, thus creating limitless possibilities for them.

I will be the first one to admit that my Chinese (Hokkien) is really just mediocre at best. I truly envy my peers who are really fluent in it. Subsequently though, I have discovered that all these languages need not be a source of struggle or insecurity by knowing their place in my life.

What I mean is I have accepted that Filipino and English will always be my mother tongue, and Chinese (Hokkien or Mandarin) would always be my second language. By simply understanding and accepting where to place them, the sense of competition among these languages will most likely dissipate and be replaced by a blanket of harmony among them.

Image: John Purget

Drawing the fine line

Finally, to answer the question “Where is this fine line between adopting your local language and preserving your own?” I say this. The image a fine line conjures is that of division and separation. As something that must not be crossed.

I believe there isn’t a fine line.

As we can see from the word “Filipino-Chinese”, there is indeed a line between the two. But it is not of division or separation but of connection. We must embrace both identities and must substantiate each with proper respect by learning and accepting its culture, traditions and language as our own.

This is my take on things. Do you have struggles with your native and ancestral language too?

Allan Ngo blogs at Money in Mandarin.